“Wow, this is easy,” he said as he shot up the hill, in a voice made squeaky by excitement. Now, he too could climb the steepest uphill slope and streak across level ground at tremendous speeds. I had plans for all the places my son and I was going to ride—distant cities, trails in the woods, hills to coast down at high speeds.

I allowed him to ride around for a few minutes, then I made him surrender the bicycle; and I put it in the garage. It was still several days until my son’s birthday, so I told him he must wipe the memory of the new bicycle from his mind so he would be surprised when he received it as a gift for his birthday. He looked at me quizzically, the way children look at their parents when they say things that make no sense, but he quickly agreed, apparently thinking he was the beneficiary of some sort of scam—but one that no one had seemed to notice and hopefully would not until it was too late. He continued to grin. I grinned too, both on the inside and on the out. I sent him into the house, and I covered his bicycle with a blanket.

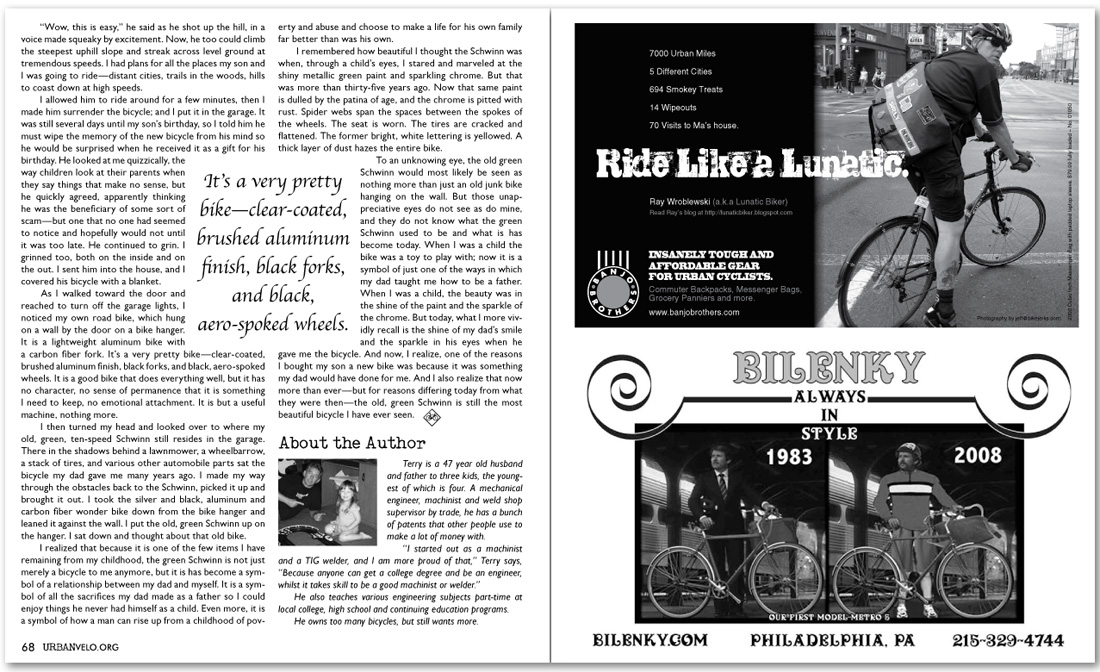

As I walked toward the door and reached to turn off the garage lights, I noticed my own road bike, which hung on a wall by the door on a bike hanger. It is a lightweight aluminum bike with a carbon fiber fork. It’s a very pretty bike—clear-coated, brushed aluminum finish, black forks, and black, aero-spoked wheels. It is a good bike that does everything well, but it has no character, no sense of permanence that it is something I need to keep, no emotional attachment. It is but a useful machine, nothing more.

I then turned my head and looked over to where my old, green, ten-speed Schwinn still resides in the garage. There in the shadows behind a lawnmower, a wheelbarrow, a stack of tires, and various other automobile parts sat the bicycle my dad gave me many years ago. I made my way through the obstacles back to the Schwinn, picked it up and brought it out. I took the silver and black, aluminum and carbon fiber wonder bike down from the bike hanger and leaned it against the wall. I put the old, green Schwinn up on the hanger. I sat down and thought about that old bike.

I realized that because it is one of the few items I have remaining from my childhood, the green Schwinn is not just merely a bicycle to me anymore, but it is has become a symbol of a relationship between my dad and myself. It is a symbol of all the sacrifices my dad made as a father so I could enjoy things he never had himself as a child. Even more, it is a symbol of how a man can rise up from a childhood of poverty and abuse and choose to make a life for his own family far better than was his own.

I remembered how beautiful I thought the Schwinn was when, through a child’s eyes, I stared and marveled at the shiny metallic green paint and sparkling chrome. But that was more than thirty-five years ago. Now that same paint is dulled by the patina of age, and the chrome is pitted with rust. Spider webs span the spaces between the spokes of the wheels. The seat is worn. The tires are cracked and flattened. The former bright, white lettering is yellowed. A thick layer of dust hazes the entire bike.

To an unknowing eye, the old green Schwinn would most likely be seen as nothing more than just an old junk bike hanging on the wall. But those unappreciative eyes do not see as do mine, and they do not know what the green Schwinn used to be and what is has become today. When I was a child the bike was a toy to play with; now it is a symbol of just one of the ways in which my dad taught me how to be a father. When I was a child, the beauty was in the shine of the paint and the sparkle of the chrome. But today, what I more vividly recall is the shine of my dad’s smile and the sparkle in his eyes when he gave me the bicycle. And now, I realize, one of the reasons I bought my son a new bike was because it was something my dad would have done for me. And I also realize that now more than ever—but for reasons differing today from what they were then—the old, green Schwinn is still the most beautiful bicycle I have ever seen.