made at a major California bank, let’s call it… Wells Fargo. I was directed to 525 Market Street and entered the lobby toward the security desk. A pudgy little man briskly moved towards me. “Go to the back of the building through the freight elevator,” states the security guard, in a tone I wouldn’t put up with from my mother. He pointed me back out the front door. “I have a pickup on the 12th floor,” I respond. “You have to go to the freight elevator,” he repeats threateningly. I walk around the building, sign in with the unenthusiastic security guard, and wait for the one, slow moving freight elevator.

Although the violation of building etiquette is innocent on my part, the violation of human respect on the part of all those security guards, receptionists, mail room clerks and all their low level ilk that messengers have to deal with every day is not innocent, but malicious. This malice is tacitly approved by the very tenants and employers in these buildings that create the circumstances to make such behavior acceptable and routine.

When I walk into a building to deliver an envelope, I’m obviously not carrying freight. It’s not like I’m holding a couple of two-by-fours. Freight elevators are for freight, since freight tends to damage delicately decorated elevators or interferes with ingress or egress by the tenants and visitors. Envelopes are not freight. Secretaries, receptionists, executives, lawyers, visitors and even mailroom clerks carry envelopes and similar parcels through the lobby every day. The requirement that I use the freight elevator is based purely on my appearance as a working person. When security guards require messengers to use the freight elevator, what they are doing is relegating low wage workers to the “servant’s entrance.”

Messenger Down

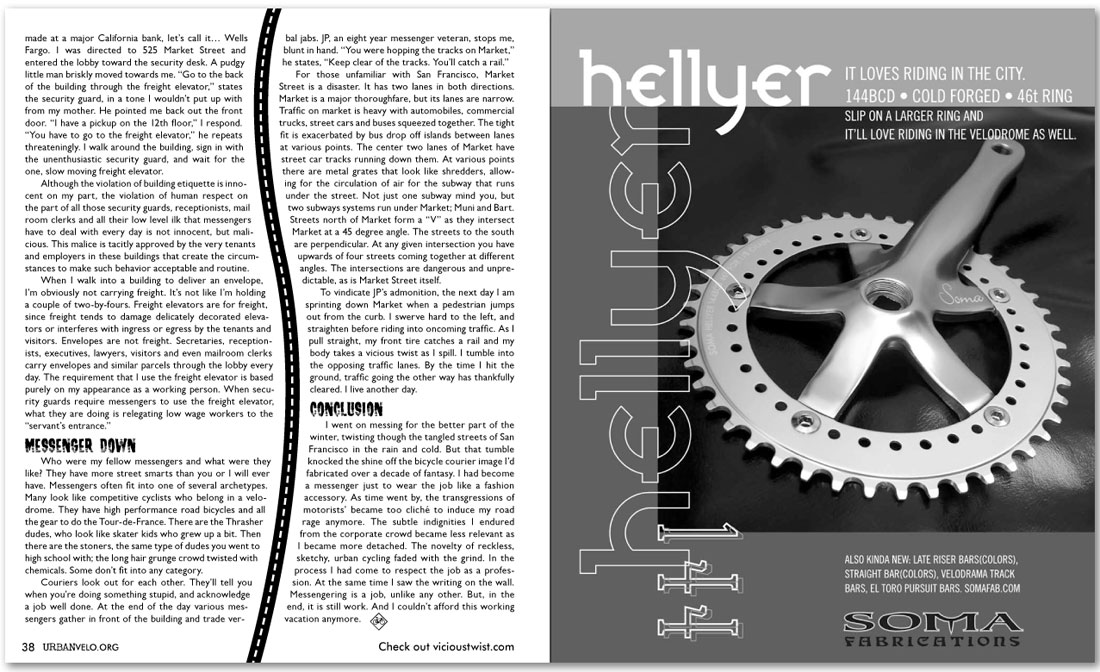

Who were my fellow messengers and what were they like? They have more street smarts than you or I will ever have. Messengers often fit into one of several archetypes. Many look like competitive cyclists who belong in a velodrome. They have high performance road bicycles and all the gear to do the Tour-de-France. There are the Thrasher dudes, who look like skater kids who grew up a bit. Then there are the stoners, the same type of dudes you went to high school with; the long hair grunge crowd twisted with chemicals. Some don’t fit into any category.

Couriers look out for each other. They’ll tell you when you’re doing something stupid, and acknowledge a job well done. At the end of the day various messengers gather in front of the building and trade verbal jabs. JP, an eight year messenger veteran, stops me, blunt in hand. “You were hopping the tracks on Market,” he states, “Keep clear of the tracks. You’ll catch a rail.”

For those unfamiliar with San Francisco, Market Street is a disaster. It has two lanes in both directions. Market is a major thoroughfare, but its lanes are narrow. Traffic on market is heavy with automobiles, commercial trucks, street cars and buses squeezed together. The tight fit is exacerbated by bus drop off islands between lanes at various points. The center two lanes of Market have street car tracks running down them. At various points there are metal grates that look like shredders, allowing for the circulation of air for the subway that runs under the street. Not just one subway mind you, but two subways systems run under Market; Muni and Bart. Streets north of Market form a “V” as they intersect Market at a 45 degree angle. The streets to the south are perpendicular. At any given intersection you have upwards of four streets coming together at different angles. The intersections are dangerous and unpredictable, as is Market Street itself.

To vindicate JP’s admonition, the next day I am sprinting down Market when a pedestrian jumps out from the curb. I swerve hard to the left, and straighten before riding into oncoming traffic. As I pull straight, my front tire catches a rail and my body takes a vicious twist as I spill. I tumble into the opposing traffic lanes. By the time I hit the ground, traffic going the other way has thankfully cleared. I live another day.

Conclusion

I went on messing for the better part of the winter, twisting though the tangled streets of San Francisco in the rain and cold. But that tumble knocked the shine off the bicycle courier image I’d fabricated over a decade of fantasy. I had become a messenger just to wear the job like a fashion accessory. As time went by, the transgressions of motorists’ became too cliché to induce my road rage anymore. The subtle indignities I endured from the corporate crowd became less relevant as I became more detached. The novelty of reckless, sketchy, urban cycling faded with the grind. In the process I had come to respect the job as a profession. At the same time I saw the writing on the wall. Messengering is a job, unlike any other. But, in the end, it is still work. And I couldn’t afford this working vacation anymore.